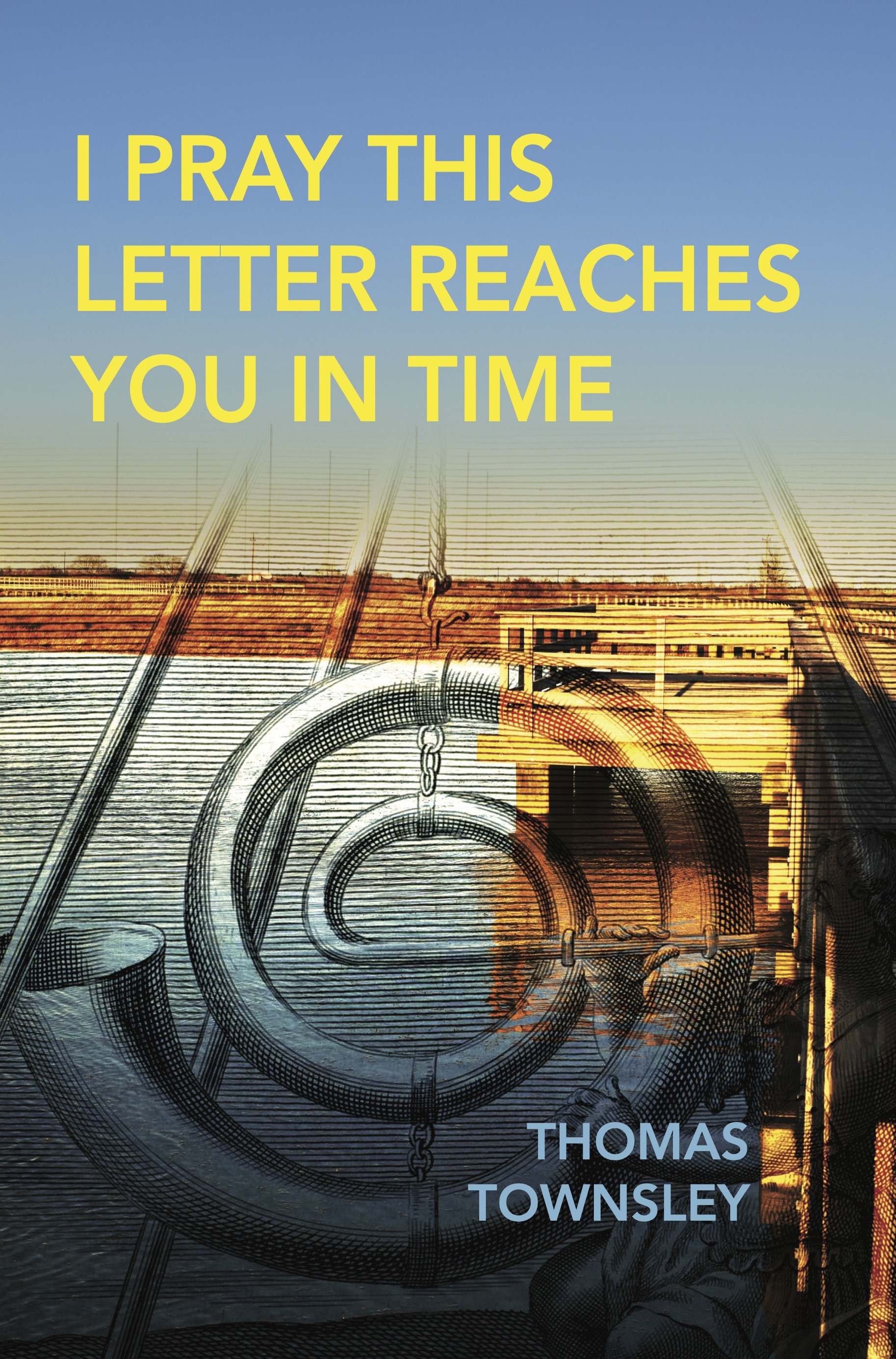

I Pray This Letter Reaches You in Time

Thomas Townsley

2022

Thomas Townsley’s fourth collection is his best yet. In poems such as “About My Last Poem” and “Summer on Neptune,” he combines esoteric ideas with humor. Despite

his often sardonic tone, one senses a deep reservoir of emotion in

these pieces. Each one ties into what Jacques Lacan called the object

petit a. Unknowable, yet inescapable, the central point of our desire drives much of our

personality and influences our experiences. Townsley has found

a way to hotwire his poems into

this zone which is usually off limits to us.

Praise for I Pray This Letter Reaches You in Time:

“I receive a letter. Inside the letter is a flyer that promises to ‘decipher the unknown.’” Thomas Townsley’s I Pray This Letter Reaches You in Time is a text-travelling, word-unravelling erotic prayfulness within a cosmic/comic playfulness. Along with the poet, we have to ask the urgent questions: “Is it possible to lie without language?//And with language, is it possible NOT to?” So true. Or definitely NOT. You see, I pray this blurb reaches this book in time. Townsley is more than a poet as he spins tunes on Neptune (see “Summer on Neptune”). He is a dada shaman communicating with the stars. He is Russell Edson writing complex, twisted parables for The Firesign Theatre; he is Salvador Dali and Ernie Kovaks rewriting Zarathustra. His poetry is meaning-shaking. It is as if he is writing inside a kaleidoscope made of firing synapses and flying fractals (see “Kaleidescape”). After I write this, I receive a letter, and inside the letter is a book, and inside the book is a poem with these words inside it: “’Shut up! Shut up!’ I cry. ‘Can’t you see I’m trying to write a poem?’”

Patrick Lawler

Author of

The Exhalation Therapist/Breathe a Wor(l)d

Tiger Bark Press

ADD TO CART ︎

Praise for I Pray This Letter Reaches You in Time:

“I receive a letter. Inside the letter is a flyer that promises to ‘decipher the unknown.’” Thomas Townsley’s I Pray This Letter Reaches You in Time is a text-travelling, word-unravelling erotic prayfulness within a cosmic/comic playfulness. Along with the poet, we have to ask the urgent questions: “Is it possible to lie without language?//And with language, is it possible NOT to?” So true. Or definitely NOT. You see, I pray this blurb reaches this book in time. Townsley is more than a poet as he spins tunes on Neptune (see “Summer on Neptune”). He is a dada shaman communicating with the stars. He is Russell Edson writing complex, twisted parables for The Firesign Theatre; he is Salvador Dali and Ernie Kovaks rewriting Zarathustra. His poetry is meaning-shaking. It is as if he is writing inside a kaleidoscope made of firing synapses and flying fractals (see “Kaleidescape”). After I write this, I receive a letter, and inside the letter is a book, and inside the book is a poem with these words inside it: “’Shut up! Shut up!’ I cry. ‘Can’t you see I’m trying to write a poem?’”

Patrick Lawler

Author of

The Exhalation Therapist/Breathe a Wor(l)d

Tiger Bark Press

ADD TO CART ︎

The Problem With Me No. 74

Time changed the lock on my youth.

Under the zeppelin’s shadow, I contemplated the irreducibility of one heart’s longing.

I once believed that the living had an advantage over the dead, in that the dead were unaware of their condition, while the living were aware of theirs. Then I began to imagine there might exist an imponderable but pervasive force to which our living blinded us, the same way death blinds the dead to consciousness.

I became a chimney sweep—I mean, a Ferris wheel operator—

I mean, a poet.

I made a sacristy of what I believed to be your eyes.

When given the opportunity, I refused to sign on the dotted line, “for the moment of a text’s inscription marks a singularity that carries with it a fissuring, a priori”—or so they said in cosmetology school.

I once held your hand in a sensory deprivation tank.

I can never get enough manna.

My past-times include winking, buffing parabolas, extorting empiricists, and bleeding on faulty syllogisms.

My imagined scenarios outnumber my real ones thirteen to one.

“Hey there, dreamer! What are you dreaming about?” the moon asked one night.

“Nothing,” I said.

“Hmm. Same here,” said the moon, and then one of us went back to sleep.

Check out Tom’s interview with Allen Guy Wilcox on Time’s Arrow Literature’s YouTube Channel.

© 2026 Doubly Mad All rights belong to the authors/artists